MAYR, E. & AMADON, D. (1951)

A Classification of Recent Birds.

American Museum Novitates 1496: 1-42.

American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Aus der Einleitung:

During the course of incorporating the Rothschild Collection of birds with the general collection of the American Museum of Natural History, an attempt was made to arrive at a natural arrangement for each family or other unit. This often led to rather detailed studies or to intensive efforts to determine the correct position of difficult genera. A number of publications growing from these studies are included in the bibliography (see titles by Amadon, Chapin, Delacour, Mayr, Vaurie, and Zimmer). They relate primarily to Old World families not yet included in Peters' "Check-list" for which no authoritative list exists comparable to Hellmayr's for the New World.

The principal purpose of this paper is to give these findings more general expression. We have of course incorporated the work of others whenever known to us and have included the non-passerine groups, although few changes are made from the now wellestablished sequence of Wetmore (1934, followed by Peters). Indeed we have throughout attempted to make no changes from the established sequence except when they are clearly indicated by recent evidence. Occasion is taken to give a corrected count of species in each family of birds; such a count proved a useful feature of a previous paper by the senior author (Mayr, 1946).

As a result of various discoveries and recent revisions the total number of species in the present list is 8590 as compared with 8616 in the previous one. The change within five years amounts to less than one-half of one per cent. Because of the large number of insular forms of doubtful status, the number of species of birds will always remain an estimate. The final figure may vary by several hundreds either way, depending on the point of view of the enumerator. The five "species" of Todus or the three of Rynchops, for example, might be considered races just as have the former "species" of Anhinga. Further study of continental forms, on the other hand, often gives clear-cut answers as to the racial or specific status of forms previously of dubious status. The result of the two recent counts indicates, however, that the final figure will be within 2 per cent of 8600. For all practical purposes this figure will be satisfactory as a very close approach to the actual number of species of living birds.

Beuteltiere - Allgemeines

Klasse: Säugetiere (Mammalia)

Unterklasse: Beutelsäuger (Metatheria)

oder:

Beuteltiere

Marsupialia • The Marsupials • Les marsupiaux

- Artenspektrum und innere Systematik

- Körperbau und Körperfunktionen

- Verbreitung

- Haltung im Zoo

- Taxonomie und Nomenklatur

- Literatur und Internetquellen

|

|

Die Beuteltiere gebären Junge, die sich noch in einem embryonalen Zustand befinden und nach der Geburt in einem Bauchbeutel fertig ausgetragen werden. Ihre Wege und die der Höheren Säugetiere haben sich zu Ende der Jurazeit – vor rund 150 Millionen Jahren - getrennt. In der nachfolgenden Evolution kam es zu zahlreichen konvergenten Entwicklungen bei den beiden Tiergruppen, z.B: Mäuse / Beutelmäuse, Goldmulle / Beutelmulle, Marder / Beutelmarder, Dachse / Beuteldachse, Wölfe / Beutelwölfe, Gleithörnchen / Gleitbeutler. Artenspektrum und innere SystematikHeute werden die 349 gegenwärtig anerkannten rezenten Arten wie folgt auf sieben Ordnungen verteilt [2; 4]:

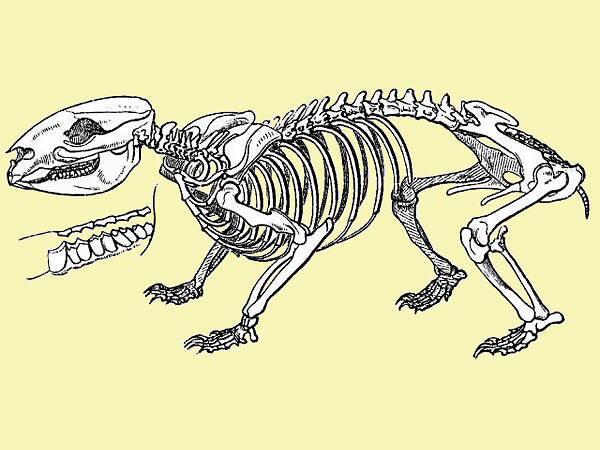

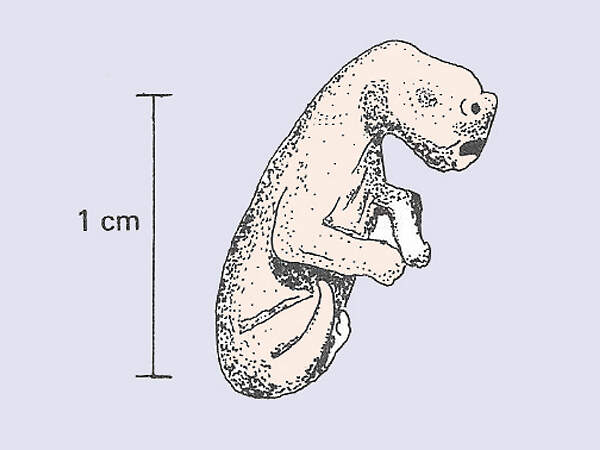

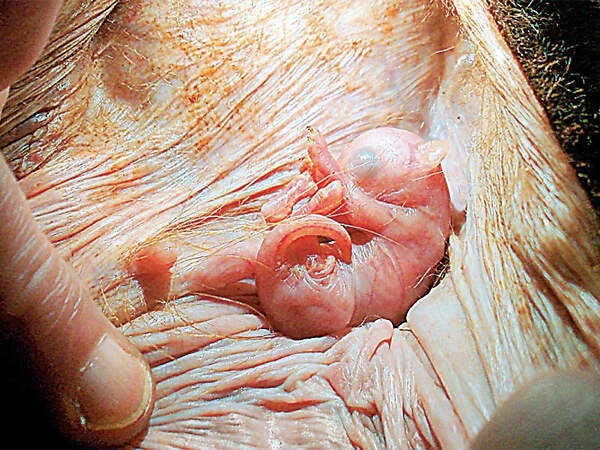

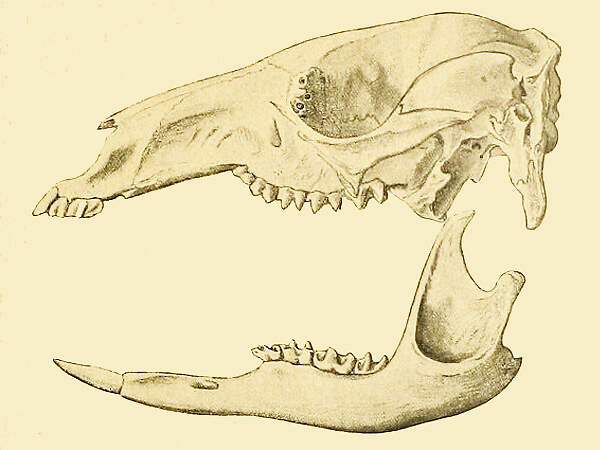

13 Arten sind seit der Besiedlung Australiens durch die Europäer ausgestorben, 12 davon im Lauf des 20. Jahrhunderts. Eine davon, der Beutelwolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus), repräsentierte eine eigene Familie. Bei den übrigen handelt es sich um 8 Kängurus, 3 Nasenbeutler sowie ein Opossum aus Argentinien [2]. Nach Roter Liste der IUCN gelten 17 der noch lebenden Arten als vom Aussterben bedroht (CRITICALLY ENDANGERED), 22 als stark gefährdet (ENDANGERED), 43 als gefährdet (VULNERABLE) und 41 als potenziell gefährdet (NEAR THREATENED). 194 sind nicht gefährdet (LEAST CONCERN) und 19 können mangels Daten nicht eingestuft werden [2]. Körperbau und KörperfunktionenDas Skelett der Beuteltiere ist säugetiertypisch. Das Rabenbein (Coracoid) ist zwar embryonal angelegt, verschmilzt dann aber mit dem Schulterblatt. In der Regel sind Schlüsselbeine vorhanden. Als Besonderheit ist bei beiden Geschlechtern in der Gegend des Schambeins ein Paar Beutelknochen (Ossa marsupialia) ausgebildet. Die Körpertemperatur ist mit 34-36°C höher als die der Kloakentiere, aber liegt unter jener der Höheren Säugetiere. Ihr Gehirn ist klein und einfach gebaut, die Großhirnhemisphären sind praktisch ungefurcht und überlappen das Kleinhirn nicht. Gut ausgebildet ist das Riechhirn. Das Gebiss kann eine sehr hohe Zahnzahl enthalten (bis 56). Außer beim 4. Prämolaren bricht nur eine Zahngeneration durch. Enddarm und Vaginalöffnungen münden in eine von einem Ringmuskel umgebene Kloakentasche, ebenso die Harnröhre, sofern sie nicht bei männlichen Tieren an der Basis des Penis mündet. Der ausschließlich samenführende Penis liegt in einer Penistasche und zwar, anders als bei den Höheren Säugetieren, nicht vor, sondern hinter dem Scrotum. Der weibliche Geschlechtsapparat ist mit unterschiedlichem Verwachsungsgrad paarig ausgebildet. Außer bei den Beuteldachsen wird keine Plazenta ausgebildet, die bis zu 11 Embryos werden von Ausscheidungen der Gebärmutterschleimhaut ernährt. Die Brutbeutel der Weibchen sind je nach Art sehr unterschiedlich. Die Zitzen sind sehr lang, damit sich die Neubegorenen an ihnen festsaugen können, vielfach kommt es zu einer sekundären Verwachsung von Jungem und Zitze. Die Jungen verlassen nach einer kurzen Tragzeit von 8-42 Tagen die Gebärmutter und werden danach im Brutbeutel untergebracht, den sie erst nach einer längeren Beuteltragzeit von bis zu 250 Tagen verlassen [1; 5]. VerbreitungSüdamerika und von dort Ausbreitung einiger Arten nach Mittel- und Nordamerika; Australien, Neuguinea, Indonesien östlich der Wallace-Linie, Salomonen. Haltung im ZooIn europäischen Zoos sind die Beuteltiere mit rund 25 Arten schwach vertreten. Das hängt damit zusammen, dass einerseits die Ausfuhr aus Australien sehr restriktiv geregelt ist, andererseits viele Arten klein und nachtaktiv sind und somit dem Publikum in Zoos nur präsentiert werden können, wenn diese über ein Nachttierhaus verfügen. Etwa die Hälfte der gezeigten Arten sind Kängurus (Macropodidae), die andere Hälfte verteilt sich auf 9 Familien. Die in Europa mit Abstand häufigste Art ist das Bennettkänguru (Macropus rufogriseus), das in rund 540 Zoos gezeigt wird, mit Abstand gefolgt vom Roten Riesenkänguru (Macropus rufus) und dem Parmakänguru (Macropus parma) mit jeweils gegen 90 Haltungen [6]. Taxonomie und NomenklaturBeuteltiere waren im Erdmittelalter und in der frühen Erdneuzeit in Nordamerika, Eurasien, Mittel- und Südamerika, der Antarktis und Afrika weit verbreitet, wurden aber bis auf die Beutelratten und Beutelmäuse in Nord- Mittel und Südamerika überall von den Höheen Säugetieren verdrängt oder wurden Opfer des Klimawandels. Nach Australien, wo wir heute die größte Artenvielfalt haben, gelangten sie, von Südamerika her, erst im Eozän, d. h. vor rund 50 Millionen Jahren [1]. Die Beutelsäuger werden als Unterklasse den Ursäugern und Höheren Säugetieren gegenüber gestellt. Früher wurden alle Beuteltiere in einer einzigen Ordnung zusammengefasst [1; 3]. HALTENORTH unterteilte 1969 die Unterklasse in mehrere Ordnungen, was in Analogie zu den Verhältnissen bei den Höheren Säugetieren durchaus gerechtfertigt ist und bis heute Bestand hat [4; 5]. |

Literatur und Internetquellen

- GRZIMEK, B. (1970). In GRZIMEKs TIERLEBEN

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. Downloaded on 6 January 2023.

- SIMPSON, G. G. (1945)

- WILSON, D. E. et al. eds. (2009-2019)

- ZISWILER, V. (1976)

- ZOOTIERLISTE

Zurück zu Übersicht Kloaken- und Beuteltiere

Weiter zu Nordopossum (Didelphis virginiana)

WADDELL, P. J., OKADA, N. & HASEGAWA, M. (1999)

Towards Resolving the Interordinal Relationships of Placental Mammals.

Systematic Biology 48 (1): 1–5.

DOI: 10.1093/sysbio/48.1.1

Einleitung:

Here we show that progress towards a reliable phylogeny for placental mammals at the ordinal level continues apace. We draw especially upon insights from the recent “International Symposium on the Origin of Mammalian Orders” held at The Graduate University of Advanced Study, Hayama, Japan (21–25 July 1998), particularly work not incorporated in the remainder of this issue or published elsewhere. Abstracts to talks and posters presented at this meeting can be found at www.utexas.edu/ftp/depts/systbiol/ . The talks fell into three main sections, which we will now consider, followed by a summary where we present our current best estimate of the tree for placental mammals.

WADDELL, P. J., KISHINO, H. & OTA, R. (2001)

A Phylogenetic Foundation for Comparative Mammalian Genomics.

Genome Informatics 12: 141–154.

Abstract:

A major effort is being undertaken to sequence an array of mammalian genomes. Coincidentally, the evolutionary relationships of the 18 presently recognized orders of placental mammals are only just being resolved. In this work we construct and analyse the largest alignments of amino acid sequence data to date. Our findings allow us to set up a series of superordinal groups (clades) to act as prior hypotheses for further testing. Important findings include strong evidence for a clade of Euarchonta+ Glires (=Supraprimates) comprised of primates, flying lemurs, tree shrews, lagomorphs and rodents. In addition, there is good evidence for a clade of all placental mammals except Xenarthra and Afrotheria (=Boreotheria) and for the previously recognised clades Laurasiatheria, Scrotifera, Fereuungulata, Ferae, Afrotheria, Euarchonta, Glires, and Eulipotyphla. Accordingly, a revised classification of the placental mammals is put forward. Using this and molecular divergence-time methods, the ages of the superordinal splits are estimated. While results are strongly consistent with the earliest superordinal divergences all being > 65 mybp (Cretaceous period), they suffer from greater uncertainty than presently appreciated. The early primate split of tarsiers from the anthropoid lineage at ∼55 mybp is seen to be an especially informative fossil calibration point. A statistical framework for testing clades using SINE data is presented and reveals significant support for the tarsier/anthropoid clade, as well as the clades Cetruminantia and Whippomorpha. Results also underline our thesis that while sequence analysis can help set up hypothesised clades, SINEs obtainable from sequencing 1-2 MB regions of placental genomes are essential to testing them. In contrast, derivations suggest that empirical Bayesian methods for sequence data may not be robust estimators of clades. Our findings, including the study of genes such as TP53, make a good case for the tree shrew as a closer relative of primates than rodents, while also showing a slower rate of evolution in key cell cycle genes. Tree shrews are consequently high value experimental animals and a strong candidate for a genome sequencing initiative.

STANHOPE, M. J., WADDELL, V. G. et al. (1998)

STANHOPE, M. J., WADDELL, V. G., MADSEN, O., DE JONG, W., BLAIR HEDGES, S., CLEVEN, G. C. , KAO, D. & SPRINGER, M. S. (1998)

Molecular evidence for multiple origins of Insectivora and for a new order of endemic African insectivore mammals.

PNAS 95 (17): 9967–9972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9967.

Abstract:

The traditional views regarding the mammalian order Insectivora are that the group descended from a single common ancestor and that it is comprised of the following families: Soricidae (shrews), Tenrecidae (tenrecs), Solenodontidae (solenodons), Talpidae (moles), Erinaceidae (hedgehogs and gymnures), and Chrysochloridae (golden moles). Here we present a molecular analysis that includes representatives of all six families of insectivores, as well as 37 other taxa representing marsupials, monotremes, and all but two orders of placental mammals. These data come from complete sequences of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA, tRNA-Valine, and 16S rRNA genes (2.6 kb). A wide range of different methods of phylogenetic analysis groups the tenrecs and golden moles (both endemic to Africa) in an all-African superordinal clade comprised of elephants, sirenians, hyracoids, aardvark, and elephant shrews, to the exclusion of the other four remaining families of insectivores. Statistical analyses reject the idea of a monophyletic Insectivora as well as traditional concepts of the insectivore suborder Soricomorpha. These findings are supported by sequence analyses of several nuclear genes presented here: vWF, A2AB, and α-β hemoglobin. These results require that the order Insectivora be partitioned and that the two African families (golden moles and tenrecs) be placed in a new order. The African superordinal clade now includes six orders of placental mammals.

Throughout most of this century, the placental (eutherian) mammals with extant representation have been classified into 18 orders. During this period, the order Insectivora has been among the least stable higher taxa in Eutheria, both in terms of phylogenetic position and taxonomic content. Beginning with Huxley (1) and later embellished by Mathew (2), insectivores have been thought to possess features that rendered them closer to the ancestral stock of mammals. Despite this presumed central position of insectivores in the evolutionary history of mammals, the composition of the group never has been widely agreed on. The prevalent morphological view (3) suggests that the following extant families of “insectivores” descended from a single common ancestor and as such should be those groups that are regarded as the constituents of the order Insectivora (Lipotyphla): Soricidae (shrews), Tenrecidae (tenrecs), Solenodontidae (solenodons), Talpidae (moles), Erinaceidae (hedgehogs and gymnures), and Chrysochloridae (golden moles).

Butler (4) listed six morphological characteristics that, in his opinion, supported a monophyletic Insectivora including (i) absence of cecum; (ii) reduction of pubic symphysis; (iii) maxillary expansion within orbit, displacing palatine; (iv) mobile proboscis; (v) reduction of jugal; and (vi) hemochorial placenta. More recently, MacPhee and Novacek (3) have reviewed the evidence and concluded that characteristics (i) and (ii) support lipotyphlan monophyly, characteristic (iii) possibly does, and (iv–vi), as currently defined, do not, leaving two to three characteristics that, in their opinion, support the order Insectivora.

The six families of insectivores are most often grouped into two clades of subordinal rank: the Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs) and the Soricomorpha (all other families). Within the Soricomorpha, Butler (4) suggested that the golden moles and tenrecs form a clade and that moles and shrews cluster together, followed by solenodons. MacPhee and Novacek (3), however, proposed three clades of subordinal rank: Chrysochloromorpha (Chrysochloridae), Erinaceomorpha (Erinaceidae), and Soricomorpha (Soricidae, Talpidae, Solenodontidae, and Tenrecidae). This latter organization is based on their view that the Chrysochloridae is “spectacularly autapomorphic.” In their opinion, golden moles show no shared derived traits with the soricomorphs and therefore should be separated from that suborder. This recommendation echoes earlier views regarding the group that have suggested that golden moles are a separate order or suborder (5–7).

A recent molecular study of mammalian phylogeny, which included three insectivore families, demonstrated that golden moles are not part of the Insectivora but instead belong to a clade of endemic African mammals that also includes elephants, hyraxes, sea cows, aardvarks, and elephant shrews (8). Evidence for this now comes from a wide range of disparate molecular loci including the nuclear AQP2, vWF, and A2AB genes as well as the mitochondrial 12S–16S rRNA genes (8, 9). The fossil record of golden moles indicates that the geographic distribution of this group has been restricted to Africa throughout its temporal range (10, 11). The fossil record of tenrecs also suggests an African origin (10, 11). This paleontological record, along with the morphological study of Butler (4), suggests a possible common ancestry for golden moles and tenrecs. However, it also may be that the autapomorphic qualities of golden moles reflect their evolutionary history as a singular distinct lineage of African insectivores, separate from the rest of the order. At present, there is no published molecular phylogenetic perspective on the evolutionary history of the Tenrecidae, there is no molecular study that includes a representative from all families of insectivores, and there are no molecular sequence data (data banks or published accounts) for solenodons.

Here, we report a molecular phylogenetic analysis involving all families of insectivores, using complete sequences of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA, and tRNA-Valine genes. These data, along with additional sequences from four disparate nuclear genes, are used to examine the extent of insectivore paraphyly or polyphyly, the conflicting hypotheses regarding the origin of the family Tenrecidae, and the possibility of an African clade of insectivores.

SPRINGER, M. S., CLEVEN, G. C. et al. (1997)

SPRINGER, M. S., CLEVEN, G. C. , MADSEN, O., DE JONG, W WADDELL, V. G., AMRINE, H. M., & STANHOPE, M. J. (1997)

Nature 388: 61-64 (3 July 1997)

Letter to Nature:

The order Insectivora, including living taxa (lipotyphlans) and archaic fossil forms, is central to the question of higher-level relationships among placental mammals1. Beginning with Huxley, it has been argued that insectivores retain many primitive features and are closer to the ancestral stock of mammals than are other living groups. Nevertheless, cladistic analysis suggests that living insectivores, at least, are united by derived anatomical features. Here we analyse DNA sequences from three mitochondrial genes and two nuclear genes to examine relationships of insectivores to other mammals. The representative insectivores are not monophyletic in any of our analyses. Rather, golden moles are included in a clade that contains hyraxes, manatees, elephants, elephant shrews and aardvarks. Members of this group are of presumed African origin. This implies that there was an extensive African radiation from a single common ancestor that gave rise to ecologically divergent adaptive types. 12S ribosomal RNA transversions suggest that the base of this radiation occurred during Africa's window of isolation in the Cretaceous period before land connections were developed with Europe in the early Cenozoic era.

SPAULDING, M., O'LEARY, M. A. & GATESY, J. (2009)

Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution.

PLoS ONE 4(9): e7062. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007062.

Abstract:

Background

Integration of diverse data (molecules, fossils) provides the most robust test of the phylogeny of cetaceans. Positioning key fossils is critical for reconstructing the character change from life on land to life in the water.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We reexamine relationships of critical extinct taxa that impact our understanding of the origin of Cetacea. We do this in the context of the largest total evidence analysis of morphological and molecular information for Artiodactyla (661 phenotypic characters and 46,587 molecular characters, coded for 33 extant and 48 extinct taxa). We score morphological data for Carnivoramorpha, †Creodonta, Lipotyphla, and the †raoellid artiodactylan †Indohyus and concentrate on determining which fossils are positioned along stem lineages to major artiodactylan crown clades. Shortest trees place Cetacea within Artiodactyla and close to †Indohyus, with †Mesonychia outside of Artiodactyla. The relationships of †Mesonychia and †Indohyus are highly unstable, however - in trees only two steps longer than minimum length, †Mesonychia falls inside Artiodactyla and displaces †Indohyus from a position close to Cetacea. Trees based only on data that fossilize continue to show the classic arrangement of relationships within Artiodactyla with Cetacea grouping outside the clade, a signal incongruent with the molecular data that dominate the total evidence result.

Conclusions/Significance

Integration of new fossil material of †Indohyus impacts placement of another extinct clade †Mesonychia, pushing it much farther down the tree. The phylogenetic position of †Indohyus suggests that the cetacean stem lineage included herbivorous and carnivorous aquatic species. We also conclude that extinct members of Cetancodonta (whales + hippopotamids) shared a derived ability to hear underwater sounds, even though several cetancodontans lack a pachyostotic auditory bulla. We revise the taxonomy of living and extinct artiodactylans and propose explicit node and stem-based definitions for the ingroup.

SIMPSON, G. G. (1945)

The principles of classification and a classification of mammals.

Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 85.

16+350 Seiten.

George Gaylord SIMPSON war Kurator für fossile Säugetiere und Vögel am Amerikanischen Museum für Naturkunde in New York. Die von ihm begründete Klassifizierung der Säugetiere hatte ein halbes Jahrhundert Bestand und wurde während dieser Zeit im Wesentlichen von den säugetierkundlichen Standardwerken übernommen. Im deutschsprachigen Raum wurde diese Systematik vor allem durch eine Veröffentlichung von MÜLLER-USING und HALTENORTH aus dem Jahr 1954, die in den „Säugetierkundlichen Mitteilungen" auf der Basis der SIMPSON’schen Klassifikation für die rezenten 22 Unter- und 10 Teilordnungen sowie für die 52 Überfamilien und 118 Familien der Säugetiere deutsche Namen vorschlugen.

simpson-biblio

O'LEARY, M. A., BLOCH, J. I. et al. (2013)

O'LEARY, M. A., BLOCH, J. I., FLYNN, J. J., GAUDIN, T. J., GIALLOMBARDO, A., GIANNINI, N. P., GOLDBERG, S. L., KRAATZ, B. P., LUO, Z.-X., MENG, J., NI, X., NOVACEK, M. J PERINI, F. A., RANDALL, Z. S., ROUGIER, G. W., SARGIS, E. J., SILCOX, M. T., SIMMONS, N. B., SPAULDING, M., VELAZCO, P. M., WEKSLER, M., WIBLE, J. R. & CIRRANELLO, A. L. (2013)

The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals.

Science (08 Feb 2013) 339 (6120): 662-667.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1229237

Abstract:

To discover interordinal relationships of living and fossil placental mammals and the time of origin of placentals relative to the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, we scored 4541 phenomic characters de novo for 86 fossil and living species. Combining these data with molecular sequences, we obtained a phylogenetic tree that, when calibrated with fossils, shows that crown clade Placentalia and placental orders originated after the K-Pg boundary. Many nodes discovered using molecular data are upheld, but phenomic signals overturn molecular signals to show Sundatheria (Dermoptera + Scandentia) as the sister taxon of Primates, a close link between Proboscidea (elephants) and Sirenia (sea cows), and the monophyly of echolocating Chiroptera (bats). Our tree suggests that Placentalia first split into Xenarthra and Epitheria; extinct New World species are the oldest members of Afrotheria.

MOUCHATY, S.K., GULLBERG, A., JANKE, A. & ARNASON, U. (2000)

The Phylogenetic Position of the Talpidae Within Eutheria Based on Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Sequences.

Molecular Biology and Evolution. 17 (1): 60–67.

ISSN 0737-4038.

Abstract:

The complete mitochondrial (mt) genome of the mole Talpa europaea was sequenced and included in phylogenetic analyses together with another lipotyphlan (insectivore) species, the hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus, and 22 other eutherian species plus three outgroup taxa (two marsupials and a monotreme). The phylogenetic analyses reconstructed a sister group relationship between the mole and the fruit bat Artibeus jamaicensis (order Chiroptera). The Talpa/Artibeus clade constitutes a sister clade of the cetferungulates, a clade including Cetacea, Artiodactyla, Perissodactyla, and Carnivora. A monophyletic relationship between the hedgehog and the mole was significantly rejected by maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood. Consistent with current systematic schemes, analyses of complete cytochrome b genes including the shrew Sorex araneus (family Soricidae) revealed a close relationship between Talpidae and Soricidae. The analyses of complete mtDNAs, along with the findings of other insectivore studies, challenge the maintenance of the order Lipotyphla as a taxonomic unit and support the elevation of the Soricomorpha (with the families Talpidae and Soricidae and possibly also the Solenodontidae and Tenrecidae) to the level of an order, as previously proposed in some morphological studies.