WALLACH, V., WÜSTER, W. & BROADLEY, D. G. (2009)

In praise of subgenera: taxonomic status of cobras of the genus Naja Laurenti (Serpentes: Elapidae).

ZOOTAXA 2236 (1): 26-36. 21 Sep. 2009.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.2236.1.2

Abstract:

The genus Naja Laurenti, 1768, is partitioned into four subgenera. The typical form is restricted to 11 Asian species. The name Uraeus Wagler, 1830, is revived for a group of four non-spitting cobras inhabiting savannas and open formations of Africa and Arabia, while Boulengerina Dollo, 1886, is applied to four non-spitting African species of forest cobras, including terrestrial, aquatic and semi-fossorial forms. A new subgenus is erected for seven species of African spitting cobras. We recommend the subgenus rank as a way of maximising the phylogenetic information content of classifications while retaining nomenclatural stability.

wallach-biblio

WÜSTER, W. et al. (2018)

Integration of nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences and morphology reveals unexpected diversity in the forest cobra (Naja melanoleuca) species complex in Central and West Africa (Serpentes: Elapidae)

Zootaxa 4455 (1): 068–098. http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/. ISSN1175-5334(online edition).

Abstract:

Cobras are among the most widely known venomous snakes, and yet their taxonomy remains incompletely understood, particularly in Africa. Here, we use a combination of mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences and morphological data to diagnose species limits within the African forest cobra, Naja (Boulengerina) melanoleuca. Mitochondrial DNA sequences reveal deep divergences within this taxon. Congruent patterns of variation in mtDNA, nuclear genes and mor-phology support the recognition of five separate species, confirming the species status of N. subfulva and N. peroescobari, and revealing two previously unnamed West African species, which are described as new: Naja (Boulengerina) guineensis sp. nov. Broadley, Trape, Chirio, Ineich & Wüster, from the Upper Guinea forest of West Africa, and Naja (Boulengerina) savannula sp. nov. Broadley, Trape, Chirio & Wüster, a banded form from the savanna-forest mosaic of the Guinea and Sudanian savannas of West Africa. The discovery of cryptic diversity in this iconic group highlights our limited under-standing of tropical African biodiversity, hindering our ability to conserve it effectively.

wüster-biblio

ARNOLD, E. N., ROBINSON, M. & CARRANZA, S. (2009)

A preliminary analysis of phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of the dangerously venomous Carpet Vipers, Echis (Squamata, Serpentes, Viperidae) based on mitochondrial DNA sequences.

Amphibia-Reptilia 30(2):273-282. DOI: 10.1163/156853809788201090.

Abstract:

Phylogenetic analysis of 1117 bp of mitochondrial DNA sequences (731 bp of cytochrome b and 386 bp of 16S rRNA) indicate that Echis consists of four main clades: E. ocellatus, and the E. coloratus, E. pyramidum, and E. carinatus groups. In the E. coloratus group, E. coloratus itself shows substantial genetic divergence from E. omanensis, corroborating their separate species status. In the E. pyramidum clade, E. pyramidum from Egypt and E. leucogaster from West Africa are genetically very similar, even though samples are separated by 4000 km. South Arabian populations of the E. pyramidum group are much better differentiated from these and two species may be present, animals from Dhofar, southern Oman probably being referable to E. khosatzkii. In the E. carinatus group, specimens of E. carinatus sochureki and E. multisquamatus are very similar in their DNA. The phylogeny indicates that the split between the main groups of Echis was followed by separation of African and Arabian members of the E. pyramidum group, and of E. coloratus and E. omanensis. The last disjunction probably took place at the lowlands that run southwest of the North Oman mountains, which are likely to have been intermittently covered by marine incursions; they also separate the E. pyramidum and E. carinatus groups and several sister taxa of other reptiles. The E. carinatus group may have spread quite recently from North Oman into its very extensive southwest Asian range, and there appears to have been similar expansion of E. pyramidum (including E. leucogaster) in North Africa. Both these events are likely to be associated with the marked climatic changes of the Pleistocene or late Pliocene. Similar dramatic expansions have also recently occurred in three snake species in Iberia.

arnold-biblio

SHINE, R. (1989)

Constraints, Allometry, and Adaptation: Food Habits and Reproductive Biology of Australian Brownsnakes (Pseudonaja: Elapidae).

Herpetologica. 45 (2): 195–207.

shine-biblio

ELS, J. & MASTENBROEK, R. (2014)

De Arabische Cobra (Naja arabica) Scortecchi 1932 in gevangenschap.

Litteratura Serpentium 34 (2): 200-215.

Introduction:

The Arabian cobra (Naja arabica) is a species that has not been noted in zoological collections or in private collections outside the countries of its natural occurrence. This species was thought to be a subspecies of the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje), but was raised at the specific rank by Trape et al. (2009). The species is categorised by IUCN as Least Concern but threats due to intense collecting for venom extraction and local animal trade markets may have serious longterm effects on wild populations (Cox, Mallon, Bowles, Els, Tognelli, 2012) Much is unknown about the species and its captive husbandry requirements. Due to a recent collaboration between the authors of two institutions a more in-depth understanding of the species captive management can be concluded to ensure their sustainable management in captive collections.

els-biblio

Tigerotter

Ordnung: Schuppenkriechtiere (SQUAMATA)

Unterordnung: Schlangen (SERPENTES)

Überfamilie: Nattern- und Vipernartige (Colubroidea oder Xenophidia)

Familie: Giftnattern (Elapidae)

Unterfamilie: Echten Giftnattern (Elapinae)

Gewöhnliche Tigerotter

Notechis scutatus • The Tiger Snake • Le serpent-tigre

- Körperbau und Körperfunktionen

- Verbreitung

- Lebensraum und Lebensweise

- Gefährdung und Schutz

- Bedeutung für den Menschen

- Haltung

- Taxonomie und Nomenklatur

- Literatur und Internetquellen

|

Weitere Bilder auf BioLib.cz |

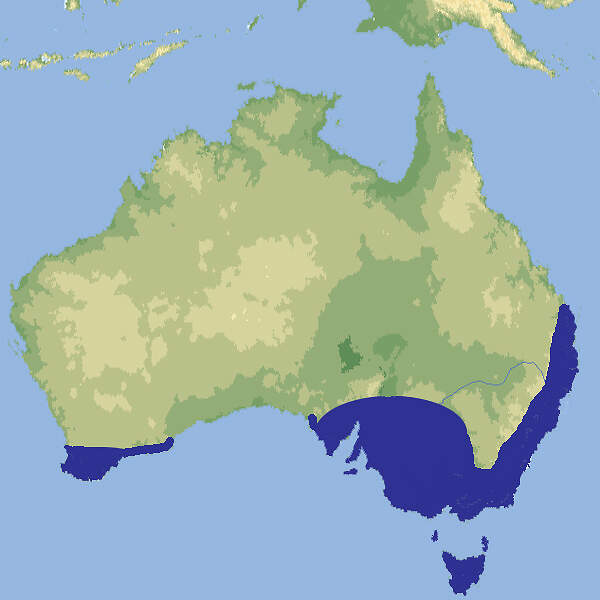

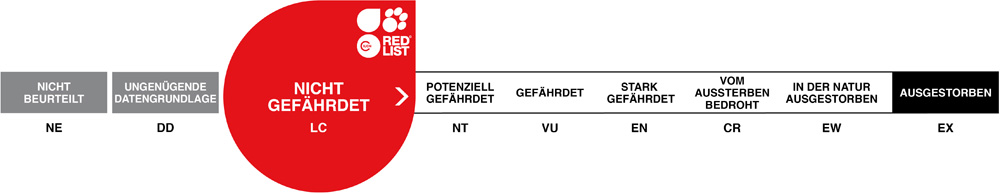

Die Tigerotter ist eine relativ kurze, etwas plumpe Giftschlange aus dem Süden Australiens, die in europäischen Zoos nur ausnahmsweise zu sehen ist. Körperbau und KörperfunktionenTigerottern werden meist etwa 1.20 m, gelegentlich bis 1.50 m lang. Sie sind kräftig gebaut, der Kopf ist kaum vom Hals abgesetzt. die Augen sind klein mit runder Pupille. Die Färbung ist sehr variabel, von hellgrau über rotbraun bis olivgrün, oft mit mehr oder weniger deutlichen hellen Querbändern. Die Unterseite ist gelb. Es gibt auch ganz schwarze Exemplare [3: 4; 6]. VerbreitungSüden und Südosten Australiens: New South Wales, Queensland, Südaustralien, Tasmanien, Westaustralien [1; 2]./span> Lebensraum und LebensweiseDie Tigerotter lebt in der Nähe von Wasserläufen, etwa in Galeriewäldern, oder auf Inseln. Sie ernährt sich hauptsächlich von Amphibien, gelegentlich von Echsen, Kleinsäugern und allenfalls Jungvögeln. Die Art ist ovovivipar. Die Würfe umfassen 10-90(-107) Junge, die bei der Geburt etwa 25 cm lang sind [2; 3; 4]. Gefährdung und SchutzEinzelne Populationen sind zwar durch intensivierte landwirtschaftliche Nutzung gefährdet. Für die Art insgesamt, die eine weite Verbreitung und einen großen Gesamtbestand hat, trifft die nach einer Beurteilung aus dem Jahr 2010 aber nicht zu [2]. Der internationale Handel ist unter CITES nicht geregelt. Es gelten Ausfuhrbeschränkungen Australien. Bedeutung für den MenschenIn Südaustralien wird ein großer Teil der Todesfälle durch Schlangenbiss durch Tigerottern verursacht [3]. HaltungDie Tigerotter gehört zu den "Gefahrtieren", deren Haltung in manchen deutschen Bundesländern unter sicherheitspolizeilichen Aspekten eingeschränkt oder geregelt ist.Die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Herpetologie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) und der Verband Deutscher Verein für Aquarien- und Terrarienkunde (DVA) haben zu dieser Thematik einen Leitfaden herausgegeben [7]. Haltung in europäischen Zoos: Die Art wird in Europa nur sporadisch gezeigt, nach 2010 gar nicht mehr. Für Details siehe Zootierliste. Mindestanforderungen an Gehege: Die Art ist weder im Reptiliengutachten 1997 des BMELF, noch in der Schweizerischen Tierschutzverordnung (Stand 01.06.2022) oder der 2. Tierhaltungsverordnung Österreichs (Stand 2023) erwähnt. Taxonomie und NomenklaturDie Art wurde 1861 von Wilhelm PETERS, der ab 1857 Direktor des Zoologischen Museums Berlin und ab demselben Jahr bis 1869 Direktor des Zoologischen Garten Berlin war, als "Naja (Hamadryas) scutata" beschrieben. Der heute gültige Name wurde 1896 von dem am British Museum tätigen belgischen Zoologen George Albert BOULENGER vergeben [6]. |

Literatur und Internetquellen

- ATLAS OF LIVING AUSTRALIA

- COGGER, H. (2010). Notechis scutatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2010: e.T169687A6666605. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/169687/0. Downloaded on 05 October 2017.

- MEHRTENS, J. M. (1993)

- O'SHEA, M. & HALLIDAY, T. (2002)

- THE REPTILE DATA BASE

- WILSON, S. & SWAN, G. (2013)

- DGHT/DVA (Hrsg. 2014)

Zurück zu Übersicht Schlangen

Weiter zu Östliche Braunschlange (Pseudonaja textilis)